Poor hip extension is a favourite of boogeyman for all manner of back and leg injuries. I have reservations about its relevance to pain and injury in terms of how the hip flexors get tight and the relevance of regional interdependence to pain (see here and here). Yet, I do not completely ignore the possibility that hip extension limitations (or not using your available hip extension) can influence function…I just think its over-rated and over used.

One area that limited hip extension is proposed to influence function is during gait. Dr. Howie Dananberg has detailed this in his theoretical ideas about how functional hallux limitus (lack of big toe dorsiflexion) leads to lack of hip extension, which in turn causes a decrease in the stretch of the psoas, leading to the loss of passive muscle recoil (because no psoas stretch) to initiate leg swing during gait and and ultimately increases in stress on the lumbar spine that leads to pain. (see a review here and one from me here). Another theory regarding running has been championed by Jay Dicharry which is slightly different and puts a strong emphasis on performance as well as the possibility of pain.

Jay Dicharry is a biomechanics researcher and physical therapist with a focus on running injuries. He runs a gait biomechanics lab at the University of Virginia (blog here) and has published some excellent reviews (here) and original research in the area (here). He has also a new book out on running injuries (here). I am a big fan of how Jay explains running biomechanics and he does an excellent job in his book. In the book he proposes a possible mechanism where lack of hip extension may negatively influence runners. Jay lays out an excellent case for how poor hip extension can compromise efficiency (I can get behind this) and may also increase injury risk (I’m still skeptical when anything comes to pain because of the complexity of the pain experience and the poor track record that biomechanics has in predicting pain but this is no fault of Jay Dicharry).

Theory in a Simplified Nutshell: Limited Hip Extension causes Overstriding.

Jay describes the swinging leg as pendulum. It has a front side swing (swinging forward to strike the ground) and a back side swing (backside mechanics that occur before the leg leaves the ground). What Jay suggests is that if you don’t have adequate hip extension the athlete will “sit back” while running and will have increased front side swing (see the picture above from www.goodguystri.ca). In other words, the pendulum arc will be shifted to the front side and the runner will land with the foot too far in front of the centre of mass - aka: overstriding. This problem will be compounded at increasing speeds when the athlete looks to increase their stride length.

Jay suggests that running in the back seat leads to two things:

- Increased metabolic cost associated with overstriding

- Increased impact loading associated with overstriding

Lets look at these two in detail.

1. Increased Metabolic cost associated with overstriding

Two mechanisms may be at a play here:

a. Lack of hip extension loses passive energy return. The muscle-tendon unit can be viewed as springs. We use the passive energy that they store rather than merely actively contracting them. The tendons store energy during impact (e.g. they start to stretch) and then they release that energy during the push off phase. With limited hip extension it is suggested that the pendulum can not swing backwards past the dashed vertical line and the pendulum must then swing forward excessively. Without the ability to swing backwards the runner doesn’t have the time to release the energy that they stored during impact because they are not able to let their leg swing backwards.

b. Overstriding is inefficient and costs more muscular work. When overstriding the center of mass of the runner increases its up and down motion. This means we work harder to decelerate the mass during impact and absorption and then we work harder to accelerate the mass during the push off phase of running. Further, with the ground striking leg being farther away from the body we are at a mechanical disadvantage for absorbing this energy. Overstriding would then increase the load on the knee and may therefore predispose individuals to knee pain.

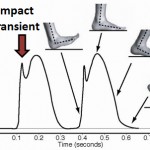

2. Increased impact loading associated with overstriding

This one  we have heard a lot and is the thrust behind shortening peoples strides, changing foot strike pattern, going barefoot or running in minimal shoes all in an attempt to decrease the rate of impact loading, collision force and joint loading when running. The closer the foot is to the center of gravity at foot strike the less rate of loading and joint loads we can expect. Heiderscheit (2011) published a recent paper showing how manipulating stride length (decreasing it) can decrease ground reaction forces, braking forces and joint loading. This is also the impetus behind Lieberman’s work championing barefoot running - he contends that the combination of a forefoot strike and a foot strike closer to the body (i.e. what occurs with shorter strides which is proposed to naturally occur when you run barefoot) decreases impact loading (a large review can be seen here).

we have heard a lot and is the thrust behind shortening peoples strides, changing foot strike pattern, going barefoot or running in minimal shoes all in an attempt to decrease the rate of impact loading, collision force and joint loading when running. The closer the foot is to the center of gravity at foot strike the less rate of loading and joint loads we can expect. Heiderscheit (2011) published a recent paper showing how manipulating stride length (decreasing it) can decrease ground reaction forces, braking forces and joint loading. This is also the impetus behind Lieberman’s work championing barefoot running - he contends that the combination of a forefoot strike and a foot strike closer to the body (i.e. what occurs with shorter strides which is proposed to naturally occur when you run barefoot) decreases impact loading (a large review can be seen here).

Other kinematic consequences of limited hip extension

Not all runners with limited hip extension will end up “sitting in the backseat”. Some can increase their backside mechanics (the range of the leg swing backwards) by arching their back. This is a common explanation we hear for the dangers of limited hip extension in runners and in all athletes or low back pain sufferers in general. In other words, if you don’t have hip mobility you steal it from somewhere else (e.g. regional interdependence). In this instance you get the range from your spine. Many authors have speculated that this increases ones risk for low back pain and for hamstring strains but again the data is not there. However, if you are having aches and pain with running this may be one area you could modify to modulate your pain response. Sometimes getting out of pain is just changing a habit, providing something new and different to our body (and brain) and you can feel less pain.

Critique and Comments

What I like about Jay Dicharry’s opinions in this areas is that he has access to data and equipment that can support his views. He is fortunate to have an impressive biomechanics laboratory and he mixes his clinical wisdom with the data is he is able to collect. Questions/ideas that this theory presents to me are:

- how regularly does a reduction in hip extension lead to overstriding? Is it really the loss of hip extension that causes overstriding or are there other variables.

-if the pendulum arc is shifted forward this implies to me that there should still be enough time for the leg to load and store elastic energy because we haven’t shortened the arc just shifted it forward with the overstride. I could see how there is less time to load and store elastic energy if the actual foot contact time was reduced because of the necessity to take a shorter stride.

-this is still an unpublished hypothesis. Like all theories of injury or performance it does need to go through rigorous testing. I look forward to seeing these concepts tested and published.

-the vast majority of people (more than 90%) probably run slower than an 8 minute mile (5 minute kilometer). Strides are typically small and there is a plenty of ground contact time. With plenty of ground contact time the athlete would be able to release that energy. With less speed there is less impact loading in general and this would provide a buffer for the slight increase in loading with the overstriding. I would question how relevant this is to contributing to injury - the simple biomechanical idea of increases loads being associated with injury is not well supported. It is not a direct relationship. In a runner with limited hip extension I would assume they have always had limited hip extension and this would have given them a lifetime to adapt. Lots of individuals run with greater impact loads and joint loading (even at the same speed) and they may not be more prone to injury - this is even what happens when we age (see a quick review here)

-I don’t doubt that people might show up with pain in their knees and also run while sitting in the back seat. I also don’t doubt that changing how they run (or stretching their hips) might be correlated with a decrease in pain. Seeing these correlations often lead us to thinking that it is the biomechanics that cause the pain when it can be many other factors. Last, even the act of changing the biomechanics can result in a resolution of pain but not because you changed the biomechanics. It can merely be the act of change, setting a new contest for running, doing a relatively novel and what is assumed to be a threat free way to run that can result in less pain.

-with respect to Performance I have little say. This is the most intriguing aspect to me. I would love to see some research showing improvements in running economy following increases in hip extension. Jay has laid out an excellent argument for how this style of gait is inefficient. This is certainly something worth tinkering with in athletes who are pushing their limits.